Explore Our Library of Resources to Help Train Your New Dog or Puppy

We want to give you as many helpful tools and tips as possible to help you with your new dog or puppy training. Once you have read through these resources, visit our dog training page to explore all of the different trainings we offer.

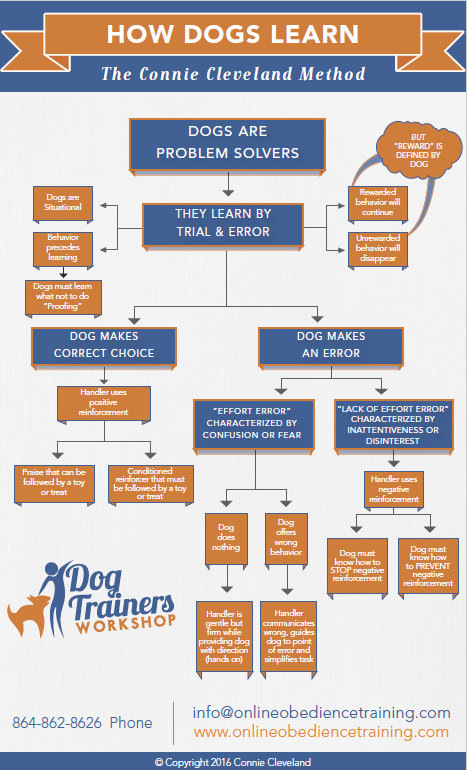

Dogs Have the Ability to Solve Problems

Dogs Have the Ability to Solve Problems

Have you ever had or seen a dog who could open the latch on his kennel run? How did he learn to do it? First, he believed he had a problem: he was locked in and could not get out. Second, he was determined to solve his problem.

Pretend that you have just rescued a 60-pound mix-breed. You brought him home and put him in a pen in your yard while you made the necessary adjustments to bring him into your home. Unhappy with his confinement, he begins to bark. There is no one around that his barking can bother, so you decide to ignore him. Sure enough, the barking stops, and on a trip by the window, you notice he is digging around the doghouse, and near the gate. “You are wasting your time,” you think, because you have placed wire under the gravel so digging will not be effective.

A short while later you notice he is on top of the doghouse, again finding no escape route. However, the next time you look outside he is gleefully running around the yard. “He has broken out!” is your first response. You examine the run, but there is no evidence of a breakout, the gate stands open. The dog is a problem solver, and he solved the problem of being confined when he did not want to be. You return him to the pen.

If you have ever experienced a dog that solved a problem by opening the latch on his kennel run, you know his second successful attempt at escape is quicker. He may briefly bark, dig, and climb, but soon he is back to jumping and pawing at the gate until he is out again.

Dogs Solve Problems by Trial and Error

This scenario demonstrates that a dog, who believes he has a problem, solves his problem by trial and error. The dog tried to solve his problem by barking, digging, and climbing before he arrived at a successful solution to his problem.

Rewarded Behavior Continues, Unrewarded Behavior Stops

This scenario also demonstrates that rewarded behavior will continue and unrewarded behavior will disappear. The dog did not continue to bark, dig, and climb. He gave up on the “solutions” that did not solve his problem. Instead, he stuck to the solutions that accomplished his goal. Remember, the reward is defined by the dog. In the sport of obedience, you may find that an unwanted behavior is self-rewarding. For example, you may be tempted to ignore a dog that is mouthing his dumbbell, and reward him only when his mouth is still. However, if he enjoys chewing the dumbbell, this technique will not work because his own enjoyment will outweigh the absence of your reward.

Dogs are Situational

Now consider that you have two pens in the backyard, and the pen that you previously used had a gate that swings from right to left. If you place the same dog, accomplished at opening that gate, in the opposite pen with a gate that swings from left to right, you will severely slow down his attempt to escape, and may even stop it completely.

Why? Because dogs are situational, they can learn to do something under one set of circumstances but not necessarily know how to do it in a slightly different set of circumstances. In this example, the dog has learned to lift the latch with his nose in one location on the gate. When placed in a pen with a gate swinging the opposite direction, he may repeatedly try to hit the hinge with his nose, bewildered as to why his behavior is not achieving the desired outcome.

For this same reason, obedience dogs fail in new locations. Just because he knows, for example, where go-out is in one ring does not mean he will know where it is in a new location or different ring.

Behavior Precedes Learning

Finally, this scenario points out that behavior precedes learning. The first time the dog opens the gate, he does it by accident. He does not understand exactly how he was successful. However, on each successive attempt, he becomes more aware of the exact behavior required. Soon you cannot turn your back before he systematically jumps up and lifts the latch with his nose.

Dogs in their own environment learn what does not work before they learn what does work. The dog in the pen “solved his problem” by trial and error. He tried digging, barking, and climbing on his doghouse. None of the behaviors solved his problem. In fact, he learned what behaviors did not work before he discovered the behavior that solved his problem.

In a training environment, we show dogs what works without giving them an opportunity to discover what does not work. You can call a dog over the broad jump hundreds of times, but if he has never tried running to you or walking through it, he truly does not understand that either of those options are not acceptable ways to solve the broad jump problem.

Dogs Must Learn What Not to Do

In order for a dog to be fully trained, he must understand how to solve his problem, and must understand what behaviors will not solve his problem. This is the definition of proofing: Shaping and luring shows dogs how to perform; proofing teaches dogs how NOT to perform.

For example, you can practice the retrieve over the high jump dozens of times and believe that you have shown your dog how to solve the problem of retrieving across a jump. However, the first time your dumbbell bounces off center, and your dog goes around the jump, he has no idea that he has not solved the problem. Going directly to the dumbbell seems logical to him, and after all, he still retrieved the dumbbell. Just like the dog in the pen, your dog must learn how to solve the off-center dumbbell problem when performing a Retrieve over the High Jump, and must also know what does not solve the problem. This is just one simple example of proofing. The same principles apply to every exercise from Novice through Utility.

If you understand that:

- Dogs are Problem Solvers

- Dogs Learn by Trial and Error

- Rewarded Behavior Continues, and Unrewarded Behavior Stops

- Dogs are Situational

- Behavior Precedes Learning

- Dogs Must Learn What Not to Do

You can use these principles to successfully train your own dog. With this information, you can present each task, or obedience exercise as a problem for the dog to solve, and then help the dog discover the appropriate solution.

Responding to Your Dog’s Behavior

As you teach your dog the steps necessary to learn the obedience exercises, he will respond correctly or incorrectly, and you must learn how to respond appropriately. By definition, reinforcement increases the likelihood that a behavior will increase in frequency and intensity. That’s the goal, correct behaviors more often with more enthusiasm.

Dog Makes the Correct Choice

Handler Uses Positive Reinforcement

When your dog performs correctly, you should respond with positive reinforcement. There is more than one way for you to provide your dog with positive reinforcement: (1) praise that can be followed by a toy or treat; and (2) a conditioned reinforcer that must be followed by a toy or treat.

Praise that Can Be Followed by a Toy or Treat

Praise “can be” followed by a toy or treat but this does not mean that praise alone cannot be positive reinforcement in the absence of a treat or toy. To be a successful performer, your dog must learn to respond to your praise absent a treat or toy.

Praise must be sincere. When you look at the dog heeling next to you, making eye contact, or the dog that is sitting where you left him after you have been out of sight for three minutes, you need to show him much you appreciate the effort he’s making. Your praise must be genuine and expressed with sincere enthusiasm. Your dog knows when you are 100% thrilled, out of your mind excited about something he’s done for you.

What makes a dog “enjoy” being praised? Any behaviorist will tell you that it’s all about pairing the praise with something the dog enjoys. That’s true, but there is more to it than that. Dogs (unlike a lizard or a snake) have a limbic part of their brain that interprets emotion. For example, when someone gives you a compliment, dopamine is released in your body. The dopamine produces excitement and makes you feel good. Dogs experience the same reaction. When you “compliment” your dog by providing positive reinforcement, dopamine is released and he becomes excited. Over time, he will learn to love activities that generate your praise.

I can’t leave the subject of praise without pointing out what praise is not.

- Praise is not obligatory. Do not say “Good Dog!” unless you mean it, if you don’t feel it, don’t waste your breath. Your dog will know that you are not sincere.

- Praise should not start wanted behaviors. Praise rewards existing behaviors. A cheerful “hurry, hurry, hurry!” does not cause a lagging dog to speed up, it tells him it is okay for him to lag.

Promise me that you will only praise with sincerity. Save your praise for the times when you are sincere and unequivocally enthusiastic about your dog’s performance. If you will do that, your dog will respond to your praise, even in the absence of the toy or treat.

A Conditioned Reinforcer Must Be Followed by a Toy or Treat

Another form of positive reinforcement is a conditioned reinforcer. Remember Pavlov’s bell? He rang the bell and the dogs drooled. The bell is a “conditioned reinforcer.” Desired behavior is reinforced or strengthened when a conditioned reinforcer is associated with a primary reinforcer (e.g., food).

A conditioned reinforcer is a noise – it can be a clicker or a distinct sound or word used to “mark” instances when your dog makes the correct choice. I use a verbal conditioned reinforcer to “mark” specific behaviors. I chose the word “Yes!” I am distinct and exude an enthusiasm that my dogs recognize when I say “Yes!” More importantly, “if I say it, I pay it!” My dogs know that when I say “Yes!” a treat is on its way — every time.

In the flow chart, I state that if the dog makes a correct choice, the handler responds with positive reinforcement. Why use a conditioned reinforcer instead of simply handing the dog a treat? Scientific studies show that a distinctive sound (a conditioned reinforcer) that precedes delivery of food (a primary reinforcer) cause dopamine and other chemicals to release in the pleasure and memory centers of the brain. These chemicals cause enjoyment and pleasure.

When a behavior consistently produces these chemicals, the subject starts to enjoy the behavior that leads to the toy or treat.

Read that sentence very carefully. Dogs (and people!) are pleasure seeking. By using a conditioned reinforcer (“Yes!”) paired with a primary reinforcer (e.g., food) you can cause a dog to enjoy the aspects of obedience that are not self-rewarding such as fronts, finishes, and pivots.

Furthermore, a conditioned reinforcer marks and rewards specific behavior. For example, if you teach your dog to run to a bed, and consistently “mark” the exact moment he puts his fourth foot on the bed, he will come to understand that it is the act of getting on the bed that causes the reward to happen. If you simply praise and feed him, he may not understand the behavior that you are rewarding because several things are happening at the same time. You are walking toward him to a deliver the treat with a pleased look on your face and he is turning on the bed, wagging his tail and waiting for you. It’s simply more difficult for a dog to ascertain exactly what behavior caused the reward. For this reason, the chemical release may not occur or is not as intense.

Be aware of some important points when using your conditioned reinforcer. Excited by your dog’s response to the distinctive sound, you may start to randomly use your verbal conditioned reinforcer and not deliver a treat. I watched a trainer heel a dog around the ring chanting “Yes!” as if she were keeping rhythm with the sound of the word. This will cause the sound to become meaningless to the dog. Thus, the term, “If you say it, you must pay it!”

Don’t bother using your conditioned reinforcer for activities the dog finds naturally rewarding. If your dog enjoys jumping, let jumping be the reward, you do not need to add anything more to the activity. Instead, use your conditioned reinforcer for the details that are hard to communicate and harder still for the dog to understand, like sitting attentively in heel position, pivoting, and then keeping his head up, straight fronts, and holding the dumbbell properly while sitting in front of you.

As dog trainers, we say, and often believe, the dog only does it “for the treat.” However, when you use a conditioned reinforcer properly, you will discover that the sequence of events that lead to the reward becomes enjoyable for your dog. Doing obedience with a dog that enjoys the activity is the most fun of all, for both of you.

Dog Makes an Incorrect Choice

If you believe that dogs are problem solvers, and they learn by trial and error, then sometimes they will make errors. How should you respond to mistakes? Not all errors are the same. Sometimes a dog makes an effort error, and sometimes they make errors due to a lack of effort.

Effort Errors, Characterized by Confusion or Fear

Effort errors are made by dogs that are attentive but appear confused, worried, or fearful. When your dog makes an effort error, he will typically offer one of two responses: (1) he does nothing; or (2) he offers the wrong behavior.

Dog Does Nothing

How should you respond to an inexperienced dog that stares intently at you but does not move when you say “Sit” or the dog that is sitting at go-out but does not move when you say “Jump”?

Dogs, like horses and goats, learn when physically moved in the correct direction. This is not true for all species. Cats do not learn by giving them direction nor do chickens or dolphins. Because your dog can learn when physically moved in the correct direction, use it to your advantage!

Be gentle, but firm as you pull up on the dog that fails to sit. When he fails to move in response to your jump command, go get him and physically guide him in the correct direction. He made an effort error and you are providing him with information about the direction in which he should move.

Dog Offers the Wrong Behavior

Dogs sometimes make effort errors by offering the wrong behavior in an attempt to solve a problem. How should you respond to the dog that heads for glove #2 when sent for glove #3 or the dog that comes straight to you when told to jump over the broad jump?

Dogs have the ability to solve problems. Offering any behavior, even a wrong one, is an attempt to solve a problem. Follow the steps outlined in the article A Simple Rule to Train By, by telling your dog he made a mistake, calmly taking him by the collar to guide him back to the position in which he was last right, and starting again by simplifying the task. By following this rule, you are telling your dog that he made a mistake and giving him another opportunity to solve the problem.

Lack of Effort Errors Characterized by Inattentiveness or Disinterest

Not all errors are committed by dogs that are attentive and trying their best. Dogs also make “lack of effort errors” because they are distracted or not interested.

Have you ever called your dog to come, seen him look in your direction, ignore your command and return to sniffing as if to say, “Just a minute, I’m busy”? Have you ever told your excited and/or distracted dog to “Sit,” only to watch him act as if he did not hear you? Have you ever given your dog a command and watched him respond as if he was not even trying to be obedient? These are all examples of “lack of effort errors.”

If you agree that lack of effort errors occur when a dog is not trying, the question becomes how to respond? Dog trainers are quick to use the word “correction.” They answer the question with a simple “I would correct my dog.” What does that mean? The word correction has been used in so many ways that it has become ambiguous. For example, if you were to tell me that your dog is running around the high jump, and ask me “How would you correct him?” I could not be sure whether you are asking me “how I would fix it” or “what kind of negative response would I use to stop him.”

I use negative reinforcement when a dog is not trying. By definition, reinforcement increases the likelihood that a behavior will occur. Negative reinforcement refers to something the dog wants to stop and wants to prevent!

For example, think about your seatbelt buzzer. That annoying sound increases the likelihood that you will buckle your seatbelt, so, by definition, it is reinforcement. It is negative because you want to make it stop. Thankfully, you know how to do so. When you hear it, buckle up. You can prevent the annoying sound by buckling your seatbelt before you start the car. You are in complete control of the annoying buzz!

How about an underground fence? Smart fence owners teach their dog how to control the sound and electric stimulus the electric fence collar provides. First, they teach their dog where the boundaries of the yard are located. Next, they walk their dog around the boundary, and when the noise occurs, they pull the dog back into the yard (dogs learn by being given direction). When done properly, the dog learns how to stop the sound and electric stimulus (the “aversive”) and how to prevent it from occurring again. The dog happily romps around the yard offering the desired behavior (staying inside the delineated boundaries) because he knows how to control the aversive.

A pop on the leash is another example of negative reinforcement. My dogs learn that a pop on the leash can be stopped by looking at me. They also know that they can avoid a pop on the leash by giving me their attention. My dogs know that they are in control of the pop and comfortably give me their full attention.

We have all seen trainers who become frustrated and lose their tempers. We have seen dogs that become nervous and scared when aversive techniques are used. This occurs when the dog does not know how to control the negative events from happening. No one is interested in making their dogs nervous or scared. In fact, we are horrified by the thought of it. That is NOT what I am talking about. I NEVER do anything that my dogs consider offensive until I have, in a calm and systematic way, taught them how to stop it and how to prevent it.

Promise me that you will never do anything to your dog that he finds offensive unless:

- He has made a “Lack of Effort Error”; and

- You have taken the time to teach him how to stop it and how to prevent it.

If you make this promise, your dog will enjoy working with you in the same way the well-trained dog enjoys romping within the confines of a yard with an underground fence.

I have been training dogs for 40 years. I have had 10 Obedience Trial Champions, 4 Field Champions, and earned numerous other titles. I have taught obedience classes in Greenville, South Carolina for over 30 years and have helped countless people earn titles on all breeds of dogs. Through it all, I have not grown tired, nor do I take for granted, the skills that dogs allow us to teach them. I have trained dogs to do obedience, fieldwork, service work, therapy work, tracking, and even some detection. No matter what I’m teaching a dog, I follow the principles outlined in this article. By presenting the task as a problem, and helping the dog solve it, I am repeatedly able to teach dogs to become good problem solvers. I am wowed every day by what dogs can learn. I hope that you are too!

Every day, dog owners call us with questions about housebreaking. Too often we hear that a dog acquired to be an indoor pet animal has been relegated to a life in the yard because he soils in the house. Our goal at the Dog Trainers Workshop is to help train dogs to be welcome and enjoyable members of the family. To do this, one of our first jobs is to help you get your dog housebroken.

Housebreaking a dog can be quite simple, if you understand some basic principles and follow some simple rules.

Dogs are naturally den animals, so a dog does not want to soil in the area where he lives. Unfortunately, most of us live in homes that are so big that the dog does not consider our entire house as his den. Therefore, it is important to keep a dog that is not housebroken in the room you are in. If you let him leave the room, he will believe that he’s left the den and that it is acceptable to soil in the room. If you are in the bedroom, shut him in the bedroom with you. If you go to the kitchen, take him with you. If it is not possible to shut a door, put up a gate, or tie him in the room with you.

Don’t watch the clock to determine when your dog needs to go outside, it is his activity that creates the need to relieve himself. It is not just how much time has elapsed. Take your dog outside every time he changes activities. If he wakes up, take him out; if he stops playing, out he goes; once he’s done eating, out again. Don’t wait, take him out before the accident occurs.

Do not think it is the dog’s responsibility to let you know when he needs to go out. Try to watch for how he signals to you that he needs to go outside. The signals may be subtle like walking toward the door or sniffing and walking in circles.

If you see your dog soil in your home in, make an exclamation of disgust and take him outside. (“No” or “Bad Dog” is sufficient.) It is not necessary to drag him to the mess or to rub his nose in it.

If your dog does soil in the house while you are not watching, there is absolutely nothing that you can do to correct the dog. Why? Dogs do not remember and feel responsible for actions in the past. If you drag a dog to an old mess and make a fuss, he does not say to himself, “I relieved myself there 20 minutes ago, that is why my owner is upset.” Instead, he records the situation in his mind, and makes sure the situation does not occur again. In this case, the dog records, “If my owner is present, and I am present, and a mess is present, I will get scolded.” The next time there is a mess on the floor and he hears you coming, he will run. Our tendency is to attribute human reasoning and emotions to our dogs. Owners call me and say, “But I know my dog knew he was bad, he ran from me and he looked guilty.” He is not running from you because he understands that he is responsible for the mess, but because he realizes that if he stays in the situation that includes himself, you, and the mess, that he will be scolded.

If you question whether this is true, pour a glass of water on the floor and talk to the dog in the same tone of voice you use when you find a mess on the floor. He will undoubtedly slink away from you just as he does when the mess is his. This should prove to you that it is not his guilt that makes him leave, but your reaction to the situation.

Your dog needs to be confined to a small area when you cannot be with him because dogs do not want to soil in the area where they live. You might try a laundry room or small bathroom, but we recommend a dog crate. A crate provides your dog with a small den of his own that he will be motivated to keep clean. Furthermore, if you leave him in a crate when you are away from him, you can be sure that nothing you care about will be chewed or destroyed while you are gone.

You may be thinking that if you keep your dog in a crate while you are at work, and again while you are sleeping, he will spend two-thirds of his life in a crate. That may be the case with a new dog who is not housebroken, but this situation won’t last long. Soon you will trust him and allow him more freedom when you are not around. Once he keeps his crate clean in your absence, try leaving him in a slightly larger space like a laundry room, porch, or kitchen. If he keeps that clean, again enlarge his space. Eventually, he will understand that your entire house is his den, and he will work to keep your home clean. Being confined for a few months of training is a small price to pay for the ability to live with a trained dog!

A few final thoughts…

If your dog consistently soils in one location in your home, this is a sign that he is attempting to keep your home clean, however he has established an indoor bathroom. Try feeding him in that location for a few days. This will cause him to reconsider his established bathroom. Most dogs will not soil where they eat.

When you let your dog out of his crate, or confined space, immediately take him outside. If he does not relieve himself outside, bring him back inside and confine him again. Wait 20-30 minutes and take him out again. Do not bring a dog inside and allow him to be loose in your house unless he has just relieved himself outside.

We often hear the complaint that an owner has put his dog out in the yard for 20-30 minutes, and as soon as they let the dog in, he has an accident. Odds are that the dog relieved himself as soon as you put him out, then sat outside the door waiting for you. Thirty minutes later, when you let him in, he needed to go again. Do not let a dog loose in your house unless he has just finished relieving himself outside.

Crates Are the Cribs and Playpens of Dog Training

A crate helps to prevent your dog from chewing and soiling the house. Crates protect dogs from consuming things in the house that could be harmful to him. A crate also calms anxious dogs and teaches hyperactive dogs to sleep when left alone. In addition, the crate becomes a home away from home whenever you are traveling with your dog.

If the crate is used correctly, your dog will regard it as a “room of his own.” It is a clean, comfortable, safe place to leave your dog when he cannot be supervised. Most dogs will try not to urinate or defecate in the crate, which is why it is so invaluable for housebreaking.

Introducing the Crate

To introduce your dog to the crate, place the crate in a “people” area such as the kitchen or family room. Use an old towel or blanket for bedding. Put your dog’s toys and a few treats in the open crate and allow your dog to come and go as he wishes. At mealtimes, feed your dog in the crate with the door closed. Clean up any spills promptly—it’s very important for the crate to stay clean! Your dog doesn’t need to stay in his crate long, but should get comfortable eating his meal there.

Put your dog in the crate when he is tired and ready for a nap. As soon as you hear him start to wake up, go to him and take him outside. Do NOT let him out if he is barking or whining because this will reward him for being noisy. Let your dog sleep in the crate at night. If he wakes you during the night, go to him and take him out. You want him to believe that you will meet his bathroom needs. However, you should return him to the crate to sleep the remainder of the night.

Leaving Your Dog in a Crate

When training is complete, how long can your dog be left? For young puppies, use this rule of thumb. The time limit should be your puppy’s age in months plus one. For example, a three-month-old pup should not be crated for more than four hours. A four-month-old

pup’s limit is five hours. The self-control of puppies varies, but most can usually hold it overnight by the age of four months. The adult dog’s self-control is usually great enough that it can be left for eight to nine hours in the crate. But keep in mind that long confinements are likely to present other mental and physical difficulties. Crate or no crate, any dog consistently denied the companionship he needs is going to be a lonely pet and may still find ways - destructive ways - to express anxiety, depression, and stress.

A dog crate offers many advantages for you and your dog—the most important being peace of mind when leaving your dog home alone. You’ll know that nothing can be soiled or destroyed, and you’ll know that your dog won’t get into anything harmful while you are gone.

Getting Started – Seven to Nine Weeks

There is probably no more exciting time in a dog owner’s life than preparing for the arrival of a new puppy. After careful consideration of what breed, what sex, which breeder, which veterinarian, what kind of food, whether to use a crate or not, you finally come to one of the most important decisions of all -- How are you going to train him?

Perhaps a bit of common sense will help you with some of these decisions. Begin by imagining how you want your adult dog to behave. The most enjoyable dog to own:

- Comes when he is called.

- Stays where he is put.

- Walks well on a leash.

- Only jumps up on people or furniture when invited.

- Plays with his toys, and leaves your stuff alone.

- Can be confined away from the family when necessary.

Think about it. If all the above statements described your dog, would you be happy? Start your training with these goals in mind as soon as you bring your puppy home.

Seven to Nine Weeks is an Infant

It is common to bring a puppy home between seven and nine weeks of age. This age is irresistible but you need to remember what an infant that little puppy is.

Feeding

There are so many dog foods; the choices are overwhelming. Ask your breeder what your puppy has been eating or discuss food types with your veterinarian. If that is not an option, buy a high quality dry food that is appropriate in its nutritional make-up and with a kibble size appropriate to the breed of your puppy. If you invest in a good quality food, it should not be necessary to give supplements to your puppy.

A seven to nine-week-old puppy will be happy to eat three times a day. It will be easier to housebreak him if he eats on a schedule, so offer him some food, and when he loses interest and wanders away, pick it up and save it for the next meal. You may want to feed him some of his meals in his crate (See Crate Training, p. 3).

It is important for you to learn what the correct weight is for your puppy. A puppy carries extra weight over his ribs, so if you cannot easily feel his ribs, your puppy is probably overweight. However, if you can see the outline of his ribs, and especially his hipbones, he is underweight. Keep in mind that as he grows, the amount of food you feed him will be changing every few weeks, so measure your food, and make it a habit to look at him and feel his ribs regularly so that you are ready to make changes as he grows.

Housebreaking

Housebreaking

It is important for your puppy to explore his new surroundings and it is fun to watch him do so. Let him look around, but remember, he will have to go outside frequently so you must keep an eye on him.

A dog is a den animal, and instinctively want to avoid soiling where they live. Unfortunately, most of us live in homes that are so big that the dog does not equate our entire house with his den. Therefore, it is important to keep any dog, and especially a puppy that is not housebroken, in the same room with you. If you let him leave the room, he will equate this with leaving the den, and think it is acceptable to soil there. So, as you let him explore, keep him in the room you are in. If you are in the bedroom, shut the bedroom door. If you go to the kitchen, take him with you. If it is not possible to shut a door, put up a gate, or use a 10-15-foot-long line to constrain him in the room with you.

Your puppy is too young to let you know when he needs to go outside. Watch for any signal that he needs to go outside. The signals may be subtle like wandering a few feet from where he was playing, sniffing, and walking in circles. Don’t make the mistake of watching the clock to determine when your puppy needs to go outside. Activity causes him to need to go outside, not the time that has elapsed. Take your puppy outside every time he changes activities. If he wakes up, take him out; stops playing, out he goes; finishes a meal, out again. Take him out before the accident occurs.

If you have a place in the yard that you would like your puppy to go use, begin by carrying him to that location and setting him down. Don’t try to walk him there. At this age, there’s a good chance it’s too far for him to travel before he stops to relieve himself. He’ll be able to make the trip himself as he gets older.

If your puppy does have a housebreaking accident right in front of you, make an exclamation of disgust and take him outside (“No” or “Bad Dog” is sufficient). It is not necessary to drag him to the mess or to rub his nose in it.

There is absolutely nothing that you can do to correct your puppy when he soils in the house while you are not watching Why? Dogs do not remember nor feel responsible for actions that occur in the past. If you drag a dog to an old mess and make a fuss, he does not say to himself, “I soiled there 20 minutes ago, and that is why my owner is upset.” Instead, he records the situation in his mind, and makes sure the situation does not occur again. In this case, the dog records, “If my owner is present, and I am present, and a mess is present, I will get scolded.” The next time he will run when there is a mess on the floor and he hears you coming.

Our tendency is to give the dog human reasoning and emotions. Owners are often heard saying, “But I know my dog knew he was bad, he ran from me, and he looked guilty.” He is not running from you because he understands that he is responsible for the mess. He runs from you because he realizes that he will be scolded if he stays in the situation that includes him, you, and the mess!

Crate Training

Crate Training

Crates are the cribs and playpens of dog training. A crate helps to prevent your dog from chewing and soiling the house. Crates protect dogs from consuming things in the house that could be harmful to them. A crate also calms anxious dogs and teaches hyperactive dogs to sleep when left alone. In addition, the crate becomes a home away from home whenever you are traveling with your dog.

Crates are not meant to be used to confine a dog for his entire lifetime any more than a playpen is used for the life of a child. They are simply a safe place for your puppy or adolescent dog to stay until he is housebroken and old enough to trust when loose in your house or yard.

When used correctly, your dog will regard his crate as a “room of his own.” A crate is a clean, comfortable, safe place to leave your dog when he cannot be supervised. Most dogs will try not to soil in their crate, which is why they are invaluable for housebreaking.

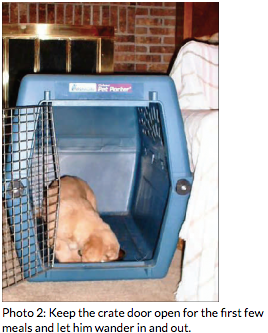

There are many types of crates, some made of plastic, some of metal, as well as varied opinions about how to introduce your dog to his crate, where to put it, whether you should have bedding, food, or toys in it, etc. The question is, what makes you comfortable?

A small puppy does not need a large crate. Just as most of us loathe laying a new infant down and listening to it scream you probably won’t want to listen to your new puppy howl in his crate. There are few noises more pitiful than a moaning puppy that has been shut in his crate before he was ready for a nap.

Introduce your dog to the crate by placing the crate in a “people” area such as the kitchen or family room. What looks comfortable to you? If your puppy seems hot natured, and the metal crate pan is cool, you may not want to put anything in the crate. If you think an old towel or blanket makes it look more appealing, then put one in there for bedding. Put your puppy’s toys and a few treats in the open crate and allow him to come and go as he wishes. At mealtimes, feed your puppy in the crate. Young puppies are sometimes slow to eat, so the first few meals you may keep the crate door open and let him wander in and out (Photo 2). When your puppy’s appetite improves, feed him with the door closed, and let him out when he’s finished. (Clean up any spills promptly—it’s very important for the crate to stay clean!) Your puppy doesn’t need to stay in his crate long, but he will become comfortable eating his meal there.

The real trick is to put your puppy in his crate when he is tired and ready for a nap. The first few nights always produce a bit of anxiety. Prepare him for bed by taking your puppy out, and playing with him until he seems ready for bed, slip him in his crate, and turn out the lights. If you had planned to put the crate in a room other than your bedroom, he may cry, and you’ll have to decide if you can stand it. However, there is nothing wrong with putting his crate next to your bed, turning out the light, and dangling your fingers through the side or door of the crate to comfort him as the two of you drift off to sleep.

If your puppy wakes you up at any time in the night, you must get up and take him out. It’s important that he learns that you will help him keep his crate clean. There is no need to play with him or feed him, simply let him soil outside, and then return him to his crate.

When you put him back in the crate, he may fuss, and you are faced with a decision. If you take him to bed with you, he will quickly learn that waking you up gets him a reward, namely the rest of the night in your bed. You should probably try to ignore him, but again, if you are soft hearted and can’t stand the whining, having the crate next to your bed where you can comfort him may be the best decision for you.

I raised a Doberman puppy who was horrible about crying and whining in her crate. I slept with the crate near my bed, and she would whine continually. I tried the crate in another room, no luck. It didn’t seem to matter how tired she was when I put her in the crate, the whining began as soon as the door was shut. Finally, in desperation, I put the crate in the car in the garage and went to bed. I’m not sure how long she whined the first night, fortunately, I could not hear her, nor could the neighbors. By the third night, she had given up her tantrums and I could bring the crate back in the house. She was finally convinced that sometimes she would have to sleep quietly when confined.

Can you ever sleep with your puppy, or allow him to nap with you? Sure. However, balance that with having him sleep in his crate. Remember your overall goal is to teach him to be confined when necessary. As he gets older, you may not use the crate to confine him. You may just want to shut him in a bedroom or out in the yard while you entertain. This is the age to begin teaching him to be confined without complaining about it.

Between seven and nine weeks, it is probably a good idea to let your puppy sleep in the crate all night, eat his meals in the crate, and stay in the crate whenever you must leave him. This may seem like a lot of “crate time,” but try to remember that this is only until your puppy gets a little older.

Between seven and nine weeks, it is probably a good idea to let your puppy sleep in the crate all night, eat his meals in the crate, and stay in the crate whenever you must leave him. This may seem like a lot of “crate time,” but try to remember that this is only until your puppy gets a little older.

Furthermore, a puppy at this age takes a lot of naps, and that is what he will learn to do whenever he is in the crate. When your puppy is comfortable with his crate, how long can he stay in his crate before he will need to go outside? Ideally, when he wakes from his nap, and cries, you will be there to take him outside. However, the answer to this question may well be dictated by your lifestyle. No one wants to leave a puppy alone all day; however, you may not have an option if you are working full-time. If that is the case, you may do better to put your puppy in a large crate, with the front half holding bedding, and the back half covered in papers so that your puppy uses the back if he must relieve himself while you are gone. This is probably a safer option than leaving him loose in a small room in your house where he could chew a piece of furniture or electric cord.

Once a young puppy is sleeping through the night, he will likely stay clean during the same amount of time during the day. The self-control of puppies varies, but almost all puppies are sleeping through the night by the age of three months. The older puppy’s self-control is usually good enough that he can spend eight to nine hours in the crate. But keep in mind that long confinements are likely to present other mental and physical difficulties. Crate or no crate, any dog consistently denied the companionship he needs is going to be a lonely pet and may still find ways - destructive ways - to express anxiety, boredom, and stress.

A small puppy comes to your home having learned to play with his littermate by chewing on them (Photo 4). Your puppy is going to chew on you. It is inevitable and it does not mean that he is a bad or aggressive puppy. He is simply trying to play with you the same way he played with his littermates.

A small puppy comes to your home having learned to play with his littermate by chewing on them (Photo 4). Your puppy is going to chew on you. It is inevitable and it does not mean that he is a bad or aggressive puppy. He is simply trying to play with you the same way he played with his littermates.

Unfortunately, his needle-sharp teeth hurt, so you will want to stop him from biting you as quickly as possible.

You are mimicking what his littermates did to him when he bit them too hard, you are biting him back, but you don’t need to use your mouth to do so. It doesn’t matter where you grab him. Young puppies have a lot of loose skin and you can grab him anywhere as you let him know that he hurt you. He should back away and look startled at your response. Your correction should be quick, and then it’s over and you can continue playing with him as you were before he bit you (Photo 5).

If you have a young child that you fear your puppy will hurt, encourage your child to play with the puppy with a toy so that the puppy has something to focus on besides the child’s clothes or hands.

If you have a young child that you fear your puppy will hurt, encourage your child to play with the puppy with a toy so that the puppy has something to focus on besides the child’s clothes or hands.

It is also inevitable that your young puppy will want to chew on your shoes, table legs, and anything else that is at his eye level. When he does, simply remove the object, or move your puppy, and give him a toy of his own. You are wasting your time by scolding him at this age, he is simply too young to care or understand why you are displeased.

Introducing Your Puppy to Other Dogs

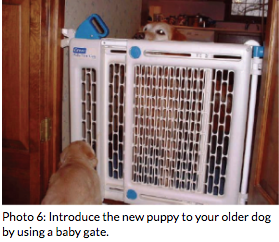

If you already have a dog, don’t be in a hurry to introduce your puppy to your older dog. This can happen gradually over the next few weeks or even months. A seven to nine-week-old puppy of any breed is so small that an older dog can hurt it, even in play.

Furthermore, if your older dog decides to discipline the puppy, there is a good chance the puppy can be seriously hurt. Let your older dog get to know the puppy by visiting with one another through a baby gate or crate. You have a whole lifetime to let them grow accustomed to one another. It doesn’t need to happen in the first few days (Photo 6).

Furthermore, if your older dog decides to discipline the puppy, there is a good chance the puppy can be seriously hurt. Let your older dog get to know the puppy by visiting with one another through a baby gate or crate. You have a whole lifetime to let them grow accustomed to one another. It doesn’t need to happen in the first few days (Photo 6).

Vaccinations and Vet Visits

Your puppy needs a series of “puppy shots” that start when he is six weeks old and end when he is four months old and able to have his first Rabies vaccine. Even if your puppy has already had his first vaccine, call your veterinarian as soon as you get him home and find out when he wants you to bring him in for his first visit. Then, be sure to follow his guidelines for his needed boosters.

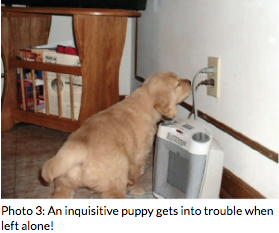

Nine Weeks to Three Months – "The Toddler"

As your puppy approaches nine weeks, you will find that he is awake more, physically more coordinated, and can see more clearly. He is becoming more inquisitive, bold, and courageous. Whereas your puppy may have followed you closely, this slightly older puppy will start to run off and feel the need to check out all that he hears and sees. Just as you would "child proof" your home if you had a toddler, you should puppy proof your home against an inquisitive puppy. Don’t leave your shoes where he can find them. Put the trash in a cabinet and encourage your children to keep their toys off the floor.

Your goal remains to have an adult dog that:

- Comes when he is called;

- Stays where he is put;

- Walks well on a leash;

- Only jumps on people or furniture when invited;

- Plays with his toys, and leaves your stuff alone; and

- Can be confined away from the family when necessary.

The biggest mistake owners make at this stage is failing to realize that they are still dealing with a very young dog. He is not yet old enough to be responsible for letting you know that he needs to go out. He does not understand which objects are his to play with and which objects are yours and off limits to him.

Continue to use a crate to confine him when you cannot keep an eye on him. When you are with him, keep your puppy in the room you are in. He is not trustworthy from a housebreaking standpoint, and you need to get him outside every time he changes activities. Furthermore, even more so than during the seven to nine-week stage, everything is going to start going in his mouth. This is the reason that he should be where you can keep an eye on him. Fortunately, he is old enough to be introduced to some of the obedience commands that you ultimately hope to teach him. So, have fun getting started!

Obedience Commands -Walking on a Leash

This is a great age to let your puppy drag a light leash or longer line (10-15 feet) around the house or yard, or when you are in a situation where he might not allow you to catch him. First, this will allow him to become accustomed to being on a leash, and will also afford you the ability to catch him if he starts to run from you.

Pick up the leash or line the puppy is dragging and follow him. This will allow your puppy to become accustomed to having someone holding on to his leash. It will give him an opportunity to learn what it is like when the two of you move together (Photo 1). At this point, it’s not necessary to insist that your puppy move in the direction that you want. Most breeds of puppies are still small enough for you to carry when they resist moving in the direction you want them to. If necessary, feel free to pick them up at this age.

Teaching "Sit"

"Sit" is an easy command to teach your puppy. Start with the treat in front of his nose and gradually tilt his head up and back toward his tail until he falls into a sitting position. As he does, tell him to sit, praise him and then give him the treat. If you lift the treat too high in the air, he will jump up for it. Your treat should be just high enough for him to reach up for it, but not so high that it makes him jump up.

Rewarding Your Puppy

To begin training your puppy to respond to simple commands, appeal to what makes your puppy happy. Most puppies are very motivated by bits of food. This is a good age for you to carry a pocket full of treats to reward him for behaviors that interest you. Training is easier if you give them soft treats they can swallow easily without having to take a lot of time to chew. If your puppy is finicky, try small bits of cheese or meat to motivate him. Consult your veterinarian if you have questions about the type of treats you should be giving to your puppy. Most people reward their puppies with much larger treats than are necessary. Find a treat you can break into very small pieces so that you don’t fill him up too quickly.

Teaching "Down"

When your puppy has mastered "Sit," it’s time to try "Down." Begin with him in a sit, and hold your treat in front of his nose. Slowly lower the treat to the ground. As his head lowers, stretch the treat out in front of him so that he walks his front legs into a down position. You may need to put your free hand on his back to keep him from standing up and walking toward the treat, but avoid the temptation to push him into a down position. Tell your puppy "Down" as he goes down, praise him, and then give him the treat for doing so.

Teaching "Come"

Start teaching your puppy to come, by calling his name and saying "Come" as you run from him. Most puppies love this game of chase and will run after you. When your puppy catches up with you, give him a treat and praise him. You may want to play this game with your puppy on a long line so that if he is distracted, you can call his name and say "Come," and then give a tug on the line to get his attention before you start to run from him.

Teaching "Kennel"

If you have been feeding your puppy in his crate, you may see him start to run ahead of you toward his crate as you prepare his meal. Tell him to "Kennel" as he jumps in to get him familiar with the "Kennel" command.

Teaching "Off"

This is an age when large breed puppies get big enough to start jumping up on things. When you sit in a chair and your puppy jumps on you, tell him "Off" and gently put your foot on his back foot. When he realizes that his foot is "trapped," he will leap off you and you can praise him and pet him for having all four feet on the ground.

If you have children, you should expect that when they run and play, your puppy will chase and jump on them. Your puppy played "chase" with his littermates and will be thrilled that there is someone in your home that knows the game!

A friend and her young daughter was coming to visit shortly after I brought my 12-week-old puppy home. I showed the little girl how to get the puppy to sit and down and encouraged her to play tug-o-war. However, every time she tried to move through the house, the puppy was right behind her trying to play by jumping on her and biting at her feet. I gave the child a squirt bottle of water set to administer a jet stream of water if she pulled the trigger. I took the child and puppy into the yard and told her to run from the puppy, and then instructed her that if the puppy touched her at all when chasing her, that she had my permission to stop running, tell him "Off," and squirt him with the water. It was no time at all before the puppy would chase her and run with her, but would not get close enough to touch her. The rest of the visit was quite peaceful as she continued to practice her sit, down, and drop commands.

Educational Games - Tug of War

Much that has been written about the horrors of playing tug-o-war with your puppy is simply not true. The only negative to playing tug-o-war is that, if you always allow him to win the game, you could create a dog that is possessive of objects.

However, playing tug-o-war gives you an opportunity to teach your puppy what "Drop" means. After you have tugged and played, stop tugging and tell your puppy to "Drop." When he does not drop the object, blow on his face. Most puppies will spit the object out and jump back from you. If blowing on his face does not cause him to spit the object out, try squeezing his front foot with your free hand. As he realizes that his foot is trapped, he will open his mouth and look down to see what’s happening (Photos 7 & 8).

Medium and large breed puppies from three-five months old are physically big enough to knock you down and chew up items you care about, but not quite old enough to understand that they shouldn’t do those things.

"Recently a young man came to see me with his 5-month old Weimaraner puppy. "He doesn’t listen to me at all. He gets so excited when he sees me that I can’t even get a leash on him. He ignores me when I say ‘no,’ and dashes around like he’s possessed. Do you think he’s stupid?" He asked. "No," I replied, "I think he sounds perfectly normal."

This is the age when you must learn to balance the behaviors you can train with those that you should manage. You will continue to train your puppy to walk on a leash, come when called, and stay where he’s put, but must realize that he is still a puppy, and will make many errors. You will simply manage his overexcitement when you have just come home after a long absence, when your guests arrive, or when he’s feeling energetic and can’t quite contain himself. He’s not old enough to have the self-control needed in those situations.

Your goal is to have your puppy learn that the leash is not on him to restrain him, but simply to keep him safe. You want a puppy that stands on a loose leash, and that looks at you when you speak or when you give a tug on the leash. You have reached an age where your puppy is ready to learn these things.

Stand with your puppy, holding the leash at a length that allows him to stand quietly beside you without getting tangled in it (Photo 1). Imagine a circle around you with a radius equal to the length of the leash. When your puppy tries to pull out of the circle, give a quick tug on the leash toward you. He may turn to look at you as if he is surprised by what happened. If he does not, reach down and poke him (Photo 2). Another puppy would nip or paw at him to get his attention and you are simply mimicking that behavior. When you have his attention, praise him and give him a treat.

If your puppy can stand on a loose leash, it’s time to teach him to walk with you on a loose leash. Tell your puppy "Let’s go," and start walking. When he runs to the end of the leash, stop and give the leash a quick tug (Photo 3). You may find it most effective to back up a few steps. If your puppy is startled enough to look at you, praise him for giving you his attention and offer him a treat.

It’s perfectly OK to stop and let your puppy sniff and investigate his surroundings. You can walk along slowly, giving him a chance to explore, much like you would take a walk with a young child. When you are ready to continue walking, repeat the command, "Let’s Go," and, if necessary, give a gentle tug to get your puppy moving.

It will be tempting to walk your puppy on a retractable leash. In your compassion you may feel that your puppy needs more room to run and explore than a short 4- to 6-foot leash will allow. The problem with this is that when your puppy is on a retractable leash, he always has the sensation that the leash is tight. You may be inadvertently teaching him that it is OK to pull you. If you want to give your puppy more freedom, use a long line. This will enable your puppy to wander farther from you and explore, and it will also give you the opportunity you need to teach him to come!

Learning to Come: The Beginning

Begin by taking your puppy out in the yard on a 15 to 20-foot rope. When he wanders away from you, say his name and the command, "Come." If he does not come, tug the leash toward you, and then back up until he catches up with you (Photo 4). Do not reach for him, as this will cause him to jump away from you after coming near. You may need to kneel down to encourage him to come all the way to you.

Inevitably, your puppy will see something that interests him and run toward it to investigate. Before he gets to the end of the rope, say his name and "Come." If he is attentive, and turns toward you, he will avoid the collar correction. However, if he is inattentive, and does not come, he will receive a tug on his collar when he gets to the end of the rope. When this occurs, encourage him to come back to you.

Soon, you will be able to walk your puppy toward another person, dog, or toy.

He will begin to stay close to you as he realizes that running off may have the negative consequences of a tug. This is the first step toward gaining off-leash control. A puppy that starts to choose to stay close to you, even though he does not feel pressure from a leash, can eventually learn to stay close to you when not on leash. You are still several months from achieving that goal, but you are headed in the right direction (Photo 5).

Learning to Stay

Puppy owners are always anxious to teach their puppies to stay. However, teaching your puppy to remain in a sit or down position for any length of time is probably going to be quite frustrating. What is easier to achieve is to teach your puppy to stay on his bed. This allows the puppy the freedom of standing, sitting or lying down, and the only rule you have to enforce is that he cannot leave the area of the bed.

Teaching "Place"

First, a bed or platform needs to be selected. The more obvious the edges are to the puppy, the easier it is to learn. Starting with a place that is a few inches off the floor or that has a raised border is easiest because once the dog steps on the place, it is very clear to him when he steps off.

Tell your dog "Place" and guide him on to it with your leash. You don’t care whether he stands, sits or lies down, so it is not necessary to give him any other command. Step away from your puppy, holding the leash as shown in photograph 6. When he steps off the place, step toward him, tell him he’s wrong, "no," and repeat "Place" as you use your leash to return him to the bed (photo 7).

Remember, your puppy is a problem solver. Just because you keep him from coming off the bed in one direction does not mean he won’t try to get off the bed in another direction. Start circling the place, stopping your puppy every time he attempts to get off. Soon he will understand where his boundaries are.

You will also need a command that lets your puppy know when it is alright to get off his bed. A simple release command, like "OK," is perfect.

When your puppy will happily stay on his bed while you are near him, it’s time to teach him to stay there even if you walk away. Begin by tying your puppy so that if he tries to follow you, the rope will stop him. Don’t tie him to the bed, as you don’t want him to drag the bed across the floor (Photo 8).

When your puppy gets off the bed, tell him he’s made a mistake by saying "no," then go to him and put him back on the bed while you repeat the command, "Place." There is no need to scream at him; a quiet, "no" will do. It probably won’t be long before he realizes that the bed is more comfortable than being stopped by the rope.

Dogs are Problem Solvers

Do not be unreasonable in the length of time that you expect your puppy to stay on the bed. Start with very short sessions, and give your puppy a toy or bone to play with while he rests on his bed. It won’t be long before you can have him remain on his bed while you eat a meal.

Hints for Sanity When Things are Difficult

Although a 3-to 5-month-old puppy is capable of learning a lot of commands, he is still a puppy and his antics will drive you crazy if you let them.

Very busy, active puppies will often start running through the house, jumping on and off furniture and creating chaos. If you frequently find yourself in a position of trying to catch your puppy, let him drag a leash in the house so that catching him becomes possible. If you are afraid that he will chew on the leash, use a piece of rope. It’s cheap, and if he chews it off, you can replace it with another.

Puppies go through stages, just like young children. It would not be uncommon for your puppy to go through a fearful period at this age. If your puppy seems to have become shy or withdrawn, maintain a very matter-of-fact attitude. Approach the object that he seems timid about with confidence. Avoid soothing him, as he will think you are praising him for his shy behavior. Instead, have an attitude that implies he should get over it and be brave!

It is common for a puppy at this stage to become housebroken. However, don’t yet let your guard down. Even though he may not soil the house, he is still very capable of being destructive in other ways. Continue to use your crate or a pen to confine him when you are away.

"Most recently my husband and I raised a Labrador Retriever puppy. Just short of his 6-month-old birthday, we started letting him sleep loose at night. He had grown accustomed to his bed, and was happy to be in the bedroom with us at night. However, he was over a year old before we trusted him to be loose in the house while we were away. There was no reason to have to come home to an unwanted mess because he had chewed a piece of furniture or shredded a magazine."

As your puppy grows, he may begin to put his front feet on your tables and counter tops. Tell him "Off" and if he fails to comply, simply touch his back foot with your foot. F